Alumni Q&A: Megan Panzano MArch ’10

Megan Panzano is an Assistant Professor of Architecture at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design (GSD), where she currently coordinates and teaches in the first semesters of the graduate and undergraduate programs. In 2016, Panzano received the Harvard Excellence in Teaching Award for her instruction in the Architecture Studies track for undergraduate students. This annual award, administered by the Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning in cooperation with the Office of the Dean of Undergraduate Education, acknowledges a select number of Harvard instructors for the excellence of their work with students and the strength of their commitment to teaching. Panzano was honored specifically for her instruction in the studio course “Transformations,” which introduces basic architectural concepts and techniques used to address issues of form, material, and the process of making. She has subsequently gone on to earn three more of these honors in sequential semesters of teaching.

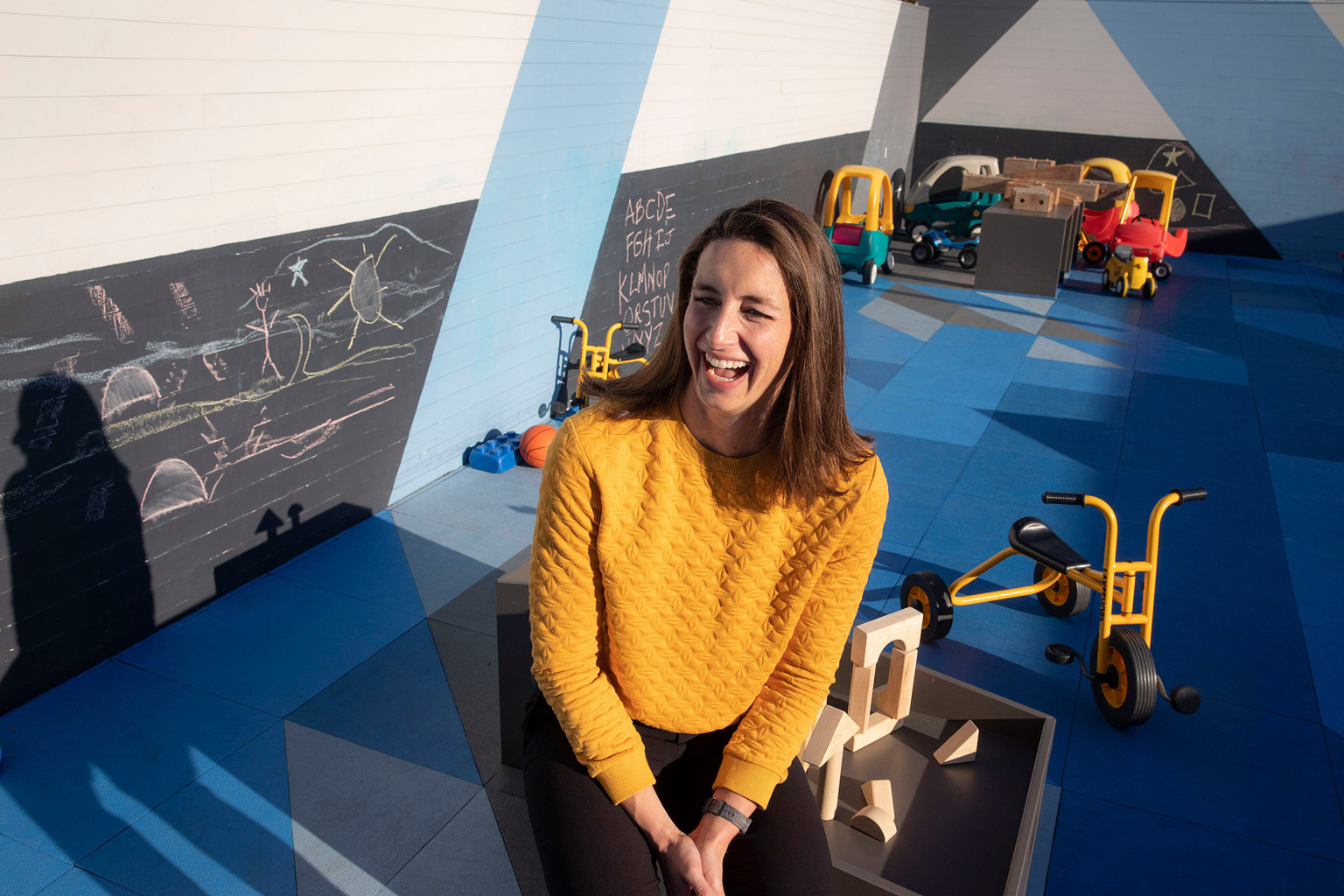

Through her independent practice, studioPM, Panzano works on an assembly of projects addressing spaces of change across a range of architectural scales. Her recent work includes “HIGH SEES,” a perceptual playground built like a boat that sits atop the roof of a preschool. She previously worked as a Senior Designer and Project Manager at Utile, Inc. and she worked closely with Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown at Venturi, Scott Brown + Associates in Philadelphia.

Panzano graduated cum laude from Yale University, earning a Bachelor of Arts in Architecture with honors in 2004. In 2010, she received her Master of Architecture with distinction from the GSD, where she was the recipient of the John E. Thayer Award for outstanding academic achievement. She was also the 2010 winner of the GSD’s James Templeton Kelley Thesis Prize for her design of a new architectural type that explored the home as an inhabitable archive—an integral site of object curation and living.

In this Q&A, Panzano shares insights into the Undergraduate Architecture Studies program, what makes the GSD MArch I model distinctive, and how she keeps busy outside of the GSD.

In this Q&A, Panzano shares insights into the Undergraduate Architecture Studies program, what makes the GSD MArch I model distinctive, and how she keeps busy outside of the GSD.

1. Tell us about your background.

I was born and raised in Atlanta, Georgia, though my family is not originally from there. This year marks my residency in the New England area for more years than my time living in the south, but those roots are still with me. I try to keep the south’s capacities for unconstrained imagination and reinvention alive as an overlay on the design work I’m thinking about and producing up here.

2. Why did you decide to come to the GSD for your Master of Architecture degree?

I have always been (and am still) drawn to the school’s interest in inviting diverse perspectives to address the project of architecture. The design departments that share the open space of Gund Hall under one roof is extraordinary. The GSD’s commitment to an academic community of students, faculty, and staff from different origins and disciplinary backgrounds weighed heavily on my decision to pursue my MArch I degree here.

3. Looking back, what experiences at the GSD were the most helpful in shaping your career?

Architecture, its education and practice across all of its outputs—research, writing, building, and curation—is a collective endeavor. The classmates I was lucky enough to share time with at the school, as well as the faculty who instructed and advised me throughout, were and, largely, are still the most influential and inspiring aspects of my experience at the GSD. Many of these individuals not only put on the map what was possible to pursue through design, but also continue to help me routinely tune-up my projects and approaches as I travel into new territory. This occurs through both direct and tangential dialogue about work. I value my GSD past and present friends and colleagues and our shared architectural productivity.

4. What about the GSD currently excites you?

The current faculty and students are smart, skilled, curious, and receptive. That’s an exciting combination, especially when channeled to design and it’s capacity to reveal and make legible to others new ways of seeing and engaging the world. In architecture, I am excited by the way the school is not compromising on what the architectural consequences of contemporary issues might be; the work of the school illustrates investment in the impact particular present issues have across all forms of design output, from representations to texts and built form and space—not just one. I think it’s important that the school continues to encourage the address of all of those things.

5. You serve as Program Director of the Undergraduate Architecture Studies program, which is part of Harvard College’s History of Art and Architecture concentration. What benefits do design thinking and studio-based courses offer to liberal arts students?

In my role as GSD Program Director of the Undergraduate Architecture Studies program over the past few years, we’ve seen a swell of interest in our undergraduate studio-based architectural design courses from students across the College, not just those within History of Art and Architecture, the concentration this track resides within. We now offer four design courses annually that are specifically crafted for undergraduates—two seminars and two studios—that are acutely aware of teaching architecture within the liberal arts context of Harvard College. Because of this, it’s intentionally not a pre-professional course of study. What we’ve promoted in these courses is the teaching through various scales of design experimentation what is specific to the discipline of architecture, with emphasis on architectural things that can productively ‘kiss’ other disciplines. Rather than a dilution of architecture amidst everything else, we teach through what is architecturally specific but more portable to other disciplines, namely the following three things: the visual representation of an idea through architectural means; the iterative process of design that is often a non-linear method of idea advancement—thinking making, analyzing and making again; and we also emphasize collaborative learning and skill-sharing in the more open environment of the design studio as an essential means of advancing architectural work. It is this set of architectural means and methods that stir creativity while managing the discipline’s complexities that these courses offer to liberal-arts studies at Harvard.

6. Tell us about your practice. In 2013, you founded studioPM, a design practice invested in research and production at multiple scales, which develops projects that carry a degree of change and instability with them. What drives your work?

Architecture consistently confronts contingencies—be they the temporality of activity, varied subjectivities, or a context in flux, in addition to the necessary budgetary ones. I am interested in anticipating what chance incidents my work may host or encounter and playfully teasing out those open-ended aspects as a medium with which to design in each project. Visual perception currently plays a big role in this. The visual images my recent work presents aspire to reveal and critique background assumptions of the link between what we see and what space and form we expect to get, playing with architecture’s representational conventions overbuilt terrain to produce spatial perceptions that differ from physical reality. Recent projects include a rooftop playground, a triptych of toys, body-sized anti-perspective image-objects, spaces for the animated collecting of things, a series of bike stops along a public trail, and a small vacation house by the beach. Each focuses on a particular friction of fixing specific architectural elements in static assembly that produce changing perceptions of form and space. This motivates the materiality, detailing, and making of each project in particular ways. Seam lines, surface hues, and textures of volumes within the architecture often overlap to align and perceptually press 3D space into planar readings that vary based on vantage point and time of day. Similarly, elements from the context are often brought into the visual field of the elements of the architecture rendering boundaries between within and without and the limit of interior space ambiguous. This recent work also intentionally experiments with the mobilization of architectures of modest size to address a range of bigger issues over larger territories.

7. You recently designed “HIGH SEES,” a 1,500-square-foot space” atop Arlington’s Learn to Grow preschool, which you call a “perceptual playground.” How did your interest in open-ended, unscripted play inform this project?

In the book Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture, Johan Huizinga describes play as intentionally useless. But, this uselessness imbues its special value. It is through its lack of prescription that play becomes a primary participant in the generation of culture. Unconstrained exploration unlocks ways of seeing the world differently, something Huizinga identifies as critical to creativity and to cultural evolution. More recent research supports this, revealing that children develop in more enriched and independent ways when given fewer guidelines for play. These sources shaped my goals for creating a space for open-ended play to promote this development through essential motor and cognitive skills for the 3-5 year old people primary to this project. In order to do so, I designed a pattern that weaves together bouncy aquatic rubber tiles with abstract custom-designed play elements to create distinct zones for unprescribed action and imagination, up on an unused roof space of the school. Its blue hues become a make-believe sea or extended sky.

The project was built to withstand two major forces: New England seasonal swings and preschoolers. 3D objects built of speedboat material for climbing on and hiding within emerge from the playground’s 2D surfaces, encouraging physical as well as visual play for its smaller occupants. Perspective views from various vantage points within the play space appear flat, contradicting the actual depth of space populated with layered elements. Carefully coordinated seams and edges cause play pieces to optically pop up from and flatten onto the floor and fence depending on the angle of view, tuning depth perception while illustrating, real-time, that the playground invites reinterpretation. Simply, what one ‘sees’ varies. The project architecturally promotes the power of play, left unscripted.

8. You were the Committee Chair for the 2019 Plimpton-Poorvu Design Prize, a prize established by GSD advocates Samuel Plimpton MBA ’77, MArch ’80 and William J. Poorvu MBA ’58. The Prize recognizes the two top teams or individuals for a viable real estate project completed as part of the GSD curricula. Why is this award important to the GSD and the study of real estate?

First, it was an enjoyable experience to serve on this prize committee because it availed me the opportunity to get to know both Sam Plimpton and Bill Poorvu and to see their commitment to the school and the support of its students first hand. This prize is particularly of note because it’s a rare award that directly encourages students to pick up and continue work initially incubated in a GSD course or studio. It is also a unique opportunity for cross-program engagement for students—applicant teams are often assembled as a mix of students from various programs to address the advancement of their design work in relation to the prize. And, lastly, the student teams advancing to the final round of consideration for this prize are supported by the close reading of their work and insightful feedback provided in rounds of review by the stellar interdepartmental prize committee composed of faculty members from across the GSD, with whom I had the honor of working closely as well.

9. You’ve taught at both Harvard and Northeastern University and served as a guest critic at many other institutions. Is the GSD studio model unique? If so, in what ways?

Speaking from within Architecture, the GSD MArch I model is something special because of the clarity and rigor of its core sequence, inclusive of both studios and complementary core courses. If we understand ‘discipline’ to be a specific branch of knowledge with distinct material and methods as means of advancement, it is clear that each semester of the GSD MArch I core sequence articulates particular disciplinary content specific to Architecture—its materials (media and scale) and methods of working. These build up in series as means to address broader issues—from techniques of architectural representation and issues of subjectivity; the complexities of identity, access, and privilege with relation to site and program; to the integration of structure and systems within the whole body of a building; and the relationship of architecture to challenges posed by the urban condition. What IS special over these semesters of the GSD’s core sequence is that architecture is not proposing to solve these bigger issues in any one investigation, but these terms work to manifest spaces that, through their design, sharpen attention to and offer new means of considering issues of contemporary relevance.

10. Where do you go to feel inspired?

Traveling anywhere new does the trick—usually including art museums. Also, hiding away and reading about architecture, and things in its orbit, in old books (that are new to me) and in contemporary journals sparks new ideas. I’m realizing that travel may be so inspiring because flying or training anywhere allows me to get a lot of reading done…

11. What’s on your reading list/watch list/playlist right now?

The journals Cabinet and Log are always top on the reading list. Currently, I’m also reading two books by Nelson Goodman: Ways of Worldmaking and Languages of Art, with particular focus on his framing of representation’s mediation of the real world. When not reading, I’ve been listening to Stevie Wonder, whose albums I recently rescued from my playlist archive, interspersed with Billie Eilish and Cautious Clay. Occasionally, I’ve been watching episodes of Parks and Recreation to lighten up my anticipation of a tricky sequence of public process presentations I have upcoming for a series of bike stops I’ve designed that require township support to move into production.

12. What would surprise us about you?

I am in the midst of training for a triathalon to have the strength and speed to keep pace with my two boys, who are 7.5 and 2.5, and both fast.