Harvard Gazette: Change is on the Runway

By Corydon Ireland, Harvard Gazette

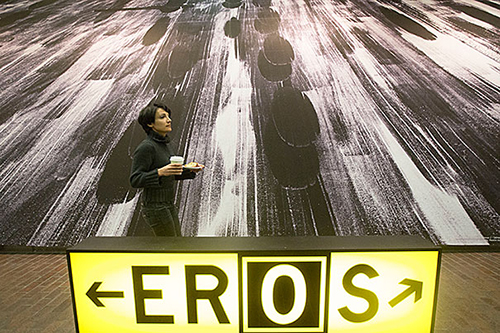

Photo: Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

In a park on the western edge of Paris in 1783, two Frenchmen stood on a platform beneath a 75-foot, hot-air balloon made of varnished taffeta. When the whimsical gold-and-blue balloon, decorated with suns and signs of the zodiac, rose into the sky, so began the world’s first free flight by humans. The balloon went up 3,000 feet, covered five miles, and landed after 25 minutes.

For a century afterward, balloon ascents around the world typically began in a city’s public gardens and parks. The notion that “flight” and “park” were logically joined lasted well into the era of powered aircraft. In the 1930s, airfields were still seen as hybrid spaces, part technical and part recreational.

Some landscape architects of the era would have continued the tradition of airfields as airparks. They were “air-minded,” said Sonja Düempelmann, associate professor of landscape architecture at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD). Their designs were influenced by traditional parks and by the modernist geometry that decades of aerial photography had revealed.

But “air-minded” landscape architects were soon pushed aside. By the mid-1930s, airports had to accommodate more powerful planes, build longer runways, handle more passengers, and deal with more cars. Since then, the airport has become, for most people, “a technical and engineering site,” said landscape architecture chair Charles Waldheim, GSD’s John E. Irving Professor. The landscape became decorative and peripheral.

But that pendulum has swung back. Airports are now more concerned about the landscape and may even become laboratories for how the cities of the future will operate, since airports have complex environments of intensive energy consumption, water use, waste generation, security concerns, transportation pressures, and commercial enterprise. “The airport itself is this nice nucleus that can act as a container of broader ideas,” said Düempelmann.

With airports emerging again as an ecological design space, Waldheim and Düempelmann organized a conference. “Airport Landscape: Urban Ecologies in the Aerial Age” unfolds Thursday and Friday at Gund Hall. At the same time, Boston is hosting the annual meeting of the American Society of Landscape Architects, with 7,000 expected to attend.

Read the entire article on Harvard Gazette.