Alumni Q&A / Dan Borelli MDes ’12, GSD Director of Exhibitions

Today, art and design find a natural home in the GSD exhibition galleries—in the course of a single year, GSD Director of Exhibitions Dan Borelli MDes ’12 and his team stage five major exhibitions and twelve smaller exhibitions featuring a wide variety of work. By providing access to the School’s rich body of design research, collaborative innovation, and impactful theory, the Druker Design Gallery and the other gallery spaces under Borelli’s purview, educate and inspire the community about the power of design through exhibits by leading designers, planners, and artists from around the world. With Gund Hall’s position along the Harvard Arts Corridor of Quincy Street, the Druker Design Gallery joins the Harvard Arts Museums and Carpenter Center which invites members of the Harvard community and beyond to the spaces and exhibitions of discourse.

Borelli is a 2012 graduate of the inaugural class of Master in Design Studies (MDes) program in Art, Design, and the Public Domain and has served as Director of Exhibition since 2000. In addition to his work inside the walls of Gund Hall, Borelli has collaborated with students on student-designed projects including a DesignMiami/ pavilion and the “WE ALL” installation in Allston. Outside of the GSD, he is deeply involved in an art-based research inquiry into an EPA Superfund Site in his hometown of Ashland, Massachusetts. To read more about Borelli’s work and what is ahead for spring exhibitions at the GSD, continue reading below.

1. Tell us about your background.

I was born in Ashland, Massachusetts and received a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Printmaking and Painting from the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). During a year studying in Rome with the RISD in Rome program, I looked at a specific set of asymmetrical paintings by Caravaggio in the Francesi Chapel. The professor who ran the Rome program was Kyna Leski MArch ’88 was a GSD alumna. During my travels, we investigated the built work of Carlo Scarpa and went to Castelvecchio, which is known as one of the finest examples of restoration architecture and exhibition design. That is when I fell in love with exhibition design and making, to see and understand materials, color, light, and space.

2. You were one of the first graduates of the MDes program in Art, Design, and the Public Domain, which seeks creative and ambitious individuals with a keen interest in contemporary issues of urban, historical, aesthetic and technological culture, and with a predilection for intervention, exhibition, and public work. Tell us about your experience with this program and how it helped to prepare you for your current role as Director of Exhibitions.

With the MDes program, I wanted to take everything I learned about exhibition making and put it into a creative practice looking at social and political issues. I posed the question about how to fuse arts administration, team building, fabrication, space making in the public space in a way that is issue-driven.

In my first semester, I took a survey class with Krzysztof Wodiczko, professor in residence of Art, Design and the Public Domain. It was his first-semester teaching, and the program was centered on the ethics of his type of practice. During the class, I was exposed to late 20th century critical writing, thinking, and practices. Instead of being gallery driven, the class was taught from an interventionist approach in the space of everyday life.

3. As part of your work in the MDes program, you started an art-based research inquiry into the Nyanza Superfund Site in your hometown, Ashland, MA, a site for the EPA’s long-term effort to clean up hazardous material contaminations. Through a combination of art, community engagement, and activism, you created a public garden memorial on the site that was once a Native American settlement. How did you involve the community to create an activist team that helps the townspeople come to grips with the severe effects water and soil contamination?

CHASING COLOR created by Dan Borelli MDes ’12.Through filters on the lights, this large-scale lighting project visualized the below-grade contaminants of environmental degradation.

In my interrogative design class, in which students investigate a big issue through a creative approach, I considered the phenomenology color, light, and space. The big issue that I raised was around the Nyanza Superfund Site in my hometown of Ashland. Massachusetts. I was previously unaware that this site was one of the first synthetic color plants for textile dyes in the United States. At this point light, color, and space morphed from phenomenology to ecology and from seducer to carcinogen for me in my project, which I called “CHASING COLOR.” What was great about the openness of the ADPD program is that I could curate my classes to match my subject. Through art-based research inquiry, I considered the mechanism in which the EPA and the federal government make knowledge public within Superfund. Through a class titled Bibliotheca, I examined how the people of Ashland are being informed regarding the toxicity in their built environment. Another Harvard connection formed when the Harvard School of Public Health began teaching a class on the cancer cluster caused by the dye contamination. At this point, I decided to apply for a Harvard Initiative for Learning and Teaching (HILT) grant for further research. With this grant funding, my research and findings were used to conduct interviews around the idea of hidden contamination became the basis of a teaching case at the School of Public Health. With making these buried narratives public, I juxtaposed the stories of human impact with the EPA’s findings on remediation.

After graduation, I received grants from Art Place America and the National Endowment of the Arts Our Town Creative Placemaking program to take the proposition that I explored in ADPD and implement it back to the public space of the town for the community to be able to viscerally experience the site of contamination. I partnered with the Arts Company and the Laborers’ International Union of North America on a multi-phase project. The first part was focused on public knowledge with an exhibition at the local library. The second was a temporary intervention in the public space to bring experiences of color back to the town; I mapped the color gradients of toxicity to the nearest streetlights. Through filters on the lights, this large-scale lighting project visualized the below-grade contaminants of environmental degradation. The third part is a permanent public garden that became a site of retreat and contemplation for the community on a two-acre site that abutted school athletic fields, which was built in partnership with the New England Laborer’s Training Academy. Also in my research, I found out that this land was an important Native American site, and I reached out to the Harvard University Native American Program to learn more. On the site used to be a meeting house for the Nipmuc tribe over 300 years ago; the tribe came to the opening of the site and performed a healing ceremony, which was very powerful. For the final phase, we are planning for a series of plantings and a public re-launching of the site following some very unfortunate community vandalism.

Upcoming event: For those in the Boston area who are interested in learning more about this project, please join Dan for “CHASING COLOR: Art and the Hidden Narratives of Industrial Waste” on Monday, February 5, 2018, at Le Laboratoire in Cambridge. More information and tickets are available at this link.

4. Tell us about your professional career. What has kept you at the GSD?

I see myself as a project person, and I love working on projects that bring people together. What is great about my role at the GSD is that exhibitions are intended to make discourse public. Very few galleries have dedicated space to architecture and design and tackle the challenging issues around the built environment that the GSD galleries address. It is infinitely fascinating.

5. In the course of a single year, you and your team stage five major exhibitions and twelve smaller exhibitions featuring a wide variety of work. How do you approach curating exhibitions at the GSD?

I see my role as being a support mechanism for the respective curatorial teams involved with us- these range from students, faculty and visiting faculty. Overall, exhibition-making is a very collaborative process with lots of discussions with faculty and leadership. I work with current and visiting faculty who deeply research their issue, and my team partners with them to help them make the most of their concept in the public space of the GSD. I see myself as a “creative producer” who translates their research and narrative in the public space of the Druker Design Gallery and view exhibitions as making public the interrelationship between concept, aesthetic and logistics. Our program follows the pedagogy of the GSD, so we aspire to be timely to issues that are important to our students.

My team is comprised of local artists, furniture makers, and craft makers. It is a good marriage between the focus of GSD faculty and students and the local Boston art scene. My team translates materials for the space and supports the local creative economy. We are constantly learning new things and being experimental. Our exhibitions in the Druker Design Gallery are built in the center of Gund Hall. Outside of the GSD, it is rare to have the opportunity to witness the process of an exhibition being built. At the GSD, students, faculty, staff, and the public are able to view the construction of an exhibition.

6. With the naming of the Druker Design Gallery, the GSD’s primary exhibition hall, do you think there will be an opportunity for a heightened impact of the Gallery space for the School, the Harvard community, and the greater Boston community?

The naming of the Druker Design Gallery is recognition of the strong and inspiring exhibitions that the GSD has produced over the years. I hope that the Gallery will gain visibility externally and encourage a broader audience to come to visit, including the local communities.

Exhibitions are fantastic opportunities for designers to test mid-scale models of their architecture and design concepts. The biggest challenge for students is that they are mostly limited to the scale of their desk or computer monitor. Students desire to test their concepts beyond this scale and to start to apply material systems and assembly logic to their ideas. It would be great if we have more funding to do more design-build projects with students.

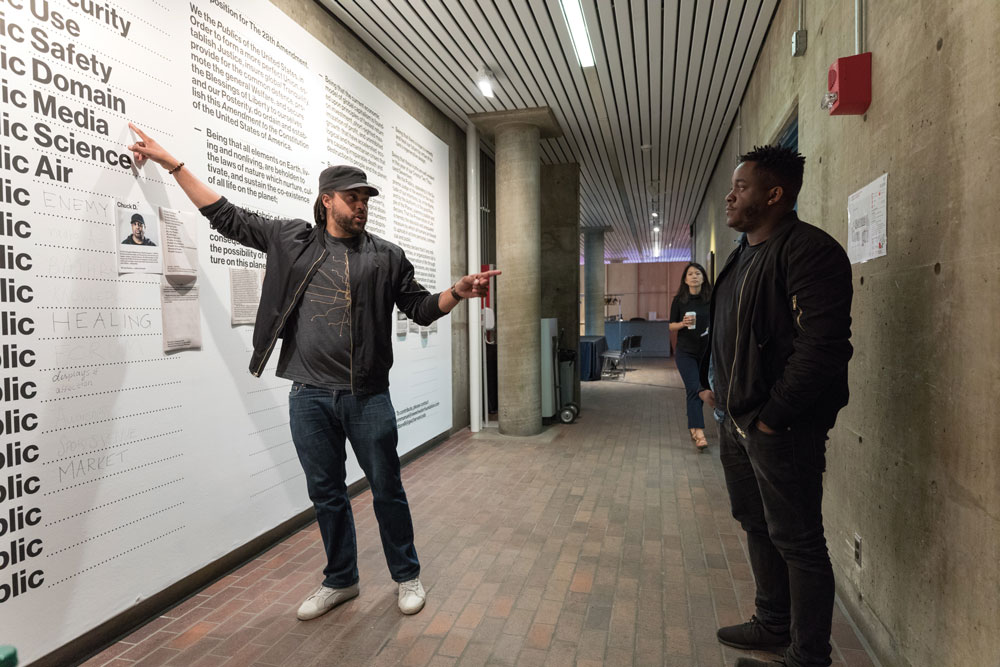

“We the Publics: A Manifesto to Restore Democracy and Truth in the Republic,” created by Emmanuel Pratt LF ’17 (left) and Dan Borelli MDes ‘12 (not pictured).

7. Your artistic process is highly collaborative and team-oriented. You created “We The Publics,” with Emmanuel Pratt LF ’17 after participating in a series of town halls, forums, and public talks within the GSD regarding the state of humanitarian and political crises. The piece was on view at the GSD in Spring 2017 and at the Smart Museum in Chicago in Fall 2017. How did you and Emmanuel decide to collaborate and what have been some of the reactions to this exhibit?

Emmanuel and I decided to explore the deeper issue of the splintering of the collective simultaneously with the pressure to move to privatization of certain basic rights that should be delivered to the collective, like clean water and education. With the presidential election, it became apparent there was a strong move to disarm the EPA and defund large urban centers that are supportive of immigration. We wanted to remind people within the GSD community that we need to speak up and create a platform for “design for all.” If we allow the current dialogue to play out without any friction, people may very quickly lose the basic human services that make society a little bit more just and equitable across socio-economic divisions. We worked with the graphic designer Andrew LeClair to make a visual installation for the “Experiment’s” wall with a provisional list of publics and prompted the community to contribute. This was one of the first times that the GSD did a participatory exhibition in which the audience helps to generate content during the duration of the exhibition. It was a way of flattening boundaries between the community. It was important for us to pluralize publics—there are multiple publics. In Chicago, the exhibit is in the entryway of the Smart Museum, and participation was strong. There are other venues that are interested so Emmanuel, and I are considering how to move it forward.

“WE ALL” designed by Master in Design Studies trio Francisco Alarcon MDes ’18, Carla Ferrer Llorca MDes ’17, and Rudy Weissenberg MDes ’18. Photo credit: Justin Knight.

8. You worked with students on a design-build competition for an installation at The Grove, located at the nexus of N. Harvard Street and Western Avenue in Allston. The chosen design “WE ALL’” created by a trio of MDes students aims to create a space together with Allston neighbors to foster commonality and connectivity while serving as a testament to the community-building powers of public art and design. What was your role in this competition and working with the selected students to bring their design to fruition?

I was approached about doing an art installation at The Grove site and worked in partnership with the Harvard University Office of the Executive Vice President, Harvard Campus Services, Harvard Planning Office, Graffito SP, and the Zone 3 initiative on the idea of doing a competition for groups of GSD students to bring design across the river. It was a wonderful marriage of interest for this parcel of land that is on the boundary between Harvard’s future campus in Allston and the existing city. The task was could the GSD do something to activate the parcel in a way that acknowledges the possible future of the campus through a transformation of space and place? We assembled a jury with GSD faculty, Harvard Campus Services, and an Allston Community Representative and we all agreed that we liked the idea of “WE ALL” as it had a very clear message with the politicization of walls and boundaries in the current US political climate. It was important for us to involve the community through interviews and open previews of the five finalists and Dan D’Oca MUP ’02 was instrumental in working with us on that process. I hope that the GSD can be involved in the transformation of other land parcels on the Allston campus.

9. As part of an Art Basel, you spoke on the panel “New Cultural Hubs: How Art Transforms Neighborhoods.” What was the most memorable part of this experience?

I think that creative practices and how they participate in shaping public space, especially in urban environments, need to be careful that they aren’t co-opted into being a tool for neo-liberal capitalists. There is now a word within the art world of “art washing” in which creative placemaking projects are made in the spirit of beautification but eradicate existing social fabrics and exhaust economic, and political divisions. It becomes a tool of gentrification. My role on this panel was to share about critical practice and how important it is for creative practices to have genuine engagement with the community or else they risk becoming a new form of exclusion and encroach on those who currently live there.

10. Can you provide a preview of what exhibitions are planned for this spring at the GSD?

The first main exhibit in the Druker Design Gallery is “Inscriptions: Architecture Before Speech,” which opened on Monday, January 22. It is curated by K. Michael Hays, Eliot Noyes Professor of Architectural Theory, and Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, and Interim Chair of the Department of Architecture; and Andrew Holder, Assistant Professor of Architecture, in collaboration with GSD Exhibitions. It has been a long time since we’ve had faculty from the world of history, theory, and criticism do a survey exhibition on architecture. Having Michael Hays and Andrew Holder curate an exhibition on contemporary architecture and culling through the work of faculty is very exciting. This exhibit makes pedagogy public—the exhibit shared important practices and important concepts.

Another exhibit coming up this spring is that Toni L. Griffin LF ’98, professor in practice of urban planning, will be sharing the work from The Just City Lab; it will be the first time that the work from her research lab will be made public to the GSD community. Also, we are working on the “Platform 10: Live Feed” exhibit with John May MArch ’02, director of the master in design studies program and assistant professor of architecture, and Jon Lott MArch ’09, assistant professor of architecture and director of the master in architecture I program, which is framing of how we engage with our own culture via feeds.

11. What would surprise us about you?

I am very close to my wife’s family who is Swedish. I speak Swedish and lived in Sweden almost a year. My daughter spends her summers there, and it has been incredible to see her confidence and engagement with another language and culture as it is an interesting comingling of cultures.