In Memoriam: Felix M. Warburg AB ’46, MArch ’51, Architect and Environmental Leader

(San Francisco)—Felix Max Warburg AB ’46, MArch ’51 of San Francisco, known to his friends as “Peter,” died at home on August 11 after 95 remarkably full years of life. An architect and lifelong environmental activist, Warburg played a significant role in designing noted public spaces and private homes in Northern California, including Ghirardelli Square and Sea Ranch, for which he served as project manager for the award-winning firm of Lawrence Halprin. He was a WW II veteran US Army intelligence officer, serving also in the Korean War, and the father of six sons and 22 grand- and great-grandchildren.

As chair of the Marin County Planning Commission in the early 1960s, Warburg pushed for creation of Point Reyes National Seashore and helped lead the successful fight against a Gulf Oil/Frouge Corporation plan to build a town of 30,000 people (“Marincello”) in what later became the open space Marin Headlands, now part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. A long-time supporter of preservation efforts, he also led Jewish history tours throughout Old West sites and helped preserve San Francisco’s Bush Street synagogue.

Felix Warburg was named for his grandfather, the noted financier and community leader whose family home on New York’s Upper East Side today houses the Jewish Museum. Felix “Peter” was born in Vienna, Austria on May 24, 1924 to parents Gerald Felix Warburg and Marian Bab of Vienna. Educated at Middlesex and Harvard, during World War II and the Korean War he twice interrupted his studies to serve as an Army intelligence officer, first 1944-46 in liberated France and occupied Germany, then at the newly built Pentagon, and finally, in 1952-3 at Camp Ritchie (later Camp David), where he taught infiltration and map reading to special forces troops prior to their deployment in Korea. The work of his WW II cohort was profiled for the 2004 documentary film The Ritchie Boys, which followed the service of German-speaking Jews in the US Army who interrogated senior Nazi officials. Warburg returned to Vienna in 1945 during his service with the U.S. Army. Attempting to find any trace of his mother’s community, he later recalled that “the only one who survived the Nazi holocaust was the doctor who delivered me.”

An undergraduate when he first enlisted, Warburg was studying to be a geologist. After witnessing the Nazis’ destruction first-hand, he resolved to be a builder. He declined recruitment into the Office of Strategic Services (later the Central Intelligence Agency) and changed his major when he returned to college in Massachusetts in 1947 as a 23-year-old sophomore. He graduated from Harvard College, then earned a degree from Harvard’s School of Architecture. The week in 1953 when he completed his second military tour, Warburg moved cross-country by train with his wife, the late Sandol Milliken Stoddard, and their two infant boys. The family initially lived in a cottage at the Alta Mira Hotel in Sausalito while he designed their first home on the newly constructed Belvedere Lagoon. The property at the end of Peninsula Road looks across the water to Mt. Tamalpais and features clean Bauhaus lines and Frank Lloyd Wright-style geometry.

Active in Marin County Democratic Party campaigns, Warburg was recruited to lead the Planning Commission at a time when the Marin County population was growing ten-fold. His efforts to block the Marincello development led to his defeat in the next election. He was later recruited to the firm of his friend Larry Halprin, who had designed the landscaping for the Warburg’s first home in Belvedere. Among the many Halprin projects Warburg aided was the Sea Ranch, the first ‘green’ development of a major residential community on the wild coastlines north of San Francisco Bay.

His second marriage in 1966 to the late Sue Rayner and move into San Francisco led to his further engagement with the City’s arts community and his interest in Jewish history from the Gold Rush era. Warburg was later appointed to the San Francisco Arts Commission by then-Mayor Dianne Feinstein. One of the projects he championed was the placement of artworks that brighten the long pedestrian concourses at the city-run San Francisco Airport. Warburg retained a lifelong commitment to environmental causes, advocating against the location of a nuclear power plant on the coastline north of Monterey Bay and for such imaginative initiatives as the use of the old Bay Bridge as armature for wind turbines and solar panels.

A poly-linguist, Warburg spoke five languages. He insisted that having casual conversations in his native German or French (which he picked up as a teenager while schooled for a time in Switzerland) “keeps your mind fresh.” After his move west in 1953, the former Boston Red Sox fan became a devoted San Francisco Giants fan who attended games from Seals Stadium to Candlestick Park to the stadium now known as Oracle Park. Asked on his 95th birthday how he always remained so cheerful, he noted wryly that “my name means ‘happy’ in Latin…and I got some of the lightness from those interwar years in Vienna, when all seemed light and cheerful.”

Warburg is survived by sons Anthony (Judy) of Sacramento, California; Peter (Melinda) of Eugene, Oregon; Gerald (Joy) of Arlington, Virginia; Jason (Karen) of Seaside, California; and Matthew (Maggie) of Seattle, Washington; sisters Geraldine Zetzel of Lexington, Massachusetts and Jeremy Warburg Russo of Newton, Massachusetts; brother Jonathan Warburg AB ’63, MArch ’68 (Stephanie) of Boston, Massachusetts; 10 grandchildren and 12 great-grandchildren. He was predeceased by his son Joshua in 1960 and his wife Susan in 2014.

Text provided by the Warburg family.

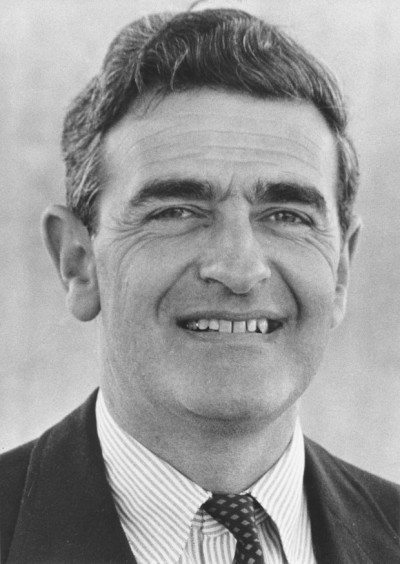

Photo: Warburg, photographed Nov. 23, 1966 (Marin Independent Journal file photo).