The Future of Air Travel: Designing a better in-flight experience

Anyone remember air travel? In early 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic swept across the globe and international flights were hurriedly cancelled, the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Laboratory for Design Technologies (LDT) pivoted its three-year focus project, The Future of Air Travel, to respond to new industry conditions in a rapidly changing world. With the broad goal of better understanding how design technologies can improve the way we live, the project aims to reimagine air travel for the future, recapturing some of its early promise (and even glamour) by assessing and addressing various pressure points resulting from the pandemic as well as more long-term challenges.

The two participating research labs—the Responsive Environments and Artifacts Lab (REAL), led by Allen Sayegh, associate professor in practice of architectural technology, and the Geometry Lab, led by Andrew Witt, associate professor in practice of architecture—“look at air travel from an experiential and a systemic perspective.” As part of their research, the labs consulted with representatives from Boeing, Clark Construction, Perkins & Will, gmp, and the Massachusetts Port Authority, all members of the GSD’s Industry Advisors Group.

Pre-COVID-19 meeting with researchers and Industry Advisors. Clockwise from far left: Bryan Kirchoff (Boeing), Hans-Joachim Paap (gmp), Jan Blasko (gmp), Isa He, Humbi Song, Stefano Andreani, Andrew Witt, and Zach Seibold. Allen Sayegh, Tobias Keyl (gmp), Kristina Loock (gmp), and Ben LeGRand (Boeing) were also in attendance.

So far, the project has resulted in two research books: the Atlas of Urban Air Mobility and On Flying: The Toolkit of Tactics that Guide Passenger Perception (and its accompanying website www.airtraveldesign.guide). On Flying, by Sayegh, REAL Research Associate Humbi Song, and Lecturer in Architecture Zach Seibold, seeks “to facilitate a rethinking of how to design objects, spaces, and systems by putting the human experience at the forefront”—and in so doing “prepare and design for improved passenger experiences in a post-COVID world.” The book’s accessible glossary covers topics including the design implications of the middle armrest (“What if armrests were shareable without physical contact?”); whether the check-in process could be improved by biometric scanners; the effect of customs declarations on passengers; how air travel is predicated on “an absence of discomfort” instead of maximizing comfort; and the metaphysical aspects of jet lag.

The project “examines and provides insight into the complex interplay of human experience, public and private systems, technological innovation, and the disruptive shock events that sometimes define the air-travel industry”. Consider, for instance, the security requirements of air travel in a post-COVID world—how can the flow of passengers through the departure/arrival process be streamlined while incorporating safety measures such social distancing?

On Flying acknowledges that it’s hard to quantify many of the designed elements—ranging from artifacts to spaces and systems—that affect our experience of air travel. So the toolkit methodically catalogs and identifies these various factors before speculating on alternative scenarios for design and passenger interaction. A year into the project, Phase 2 will more overtly examine the context of COVID-19, considering it alongside other catastrophic events, such as 9/11, in order to better understand and plan for their impact on the industry as a whole and on passenger behavior.

Meanwhile, the Atlas of Urban Air Mobility, by Witt and Lecturer in Architecture Hyojin Kwon, is “a collection of the dimensional and spatial parameters that establish relationships between aerial transport and the city,” and it aims to establish a “kit of parts” for the aerial city of the future. Phase 1 considered the idea of new super-conglomerates of cities, dependent on inter-connectivity of air routes—specifically looking at the unique qualities of Florida as an air travel hub. The atlas investigates flightpath planning and noise pollution and other spatial constraints of air travel within urban environments. One possible solution it raises is the concept of “clustered networks,” where electrical aerial vehicles could be used in an interconnected pattern of local urban conurbations, reflecting a hierarchy of passenger flight, depending on scale and distance traveled.

Phase 2 will move into software and atlas development, expanding the atlas as well as their simulation and planning software. One intriguing aspect will be a critical history of past visions of future air travel: a chance to look back in order to look forward with fresh eyes. By studying our shared dream of air travel, the hope is to rediscover and reboot abandoned visions that may yet prove to inspire new innovations.

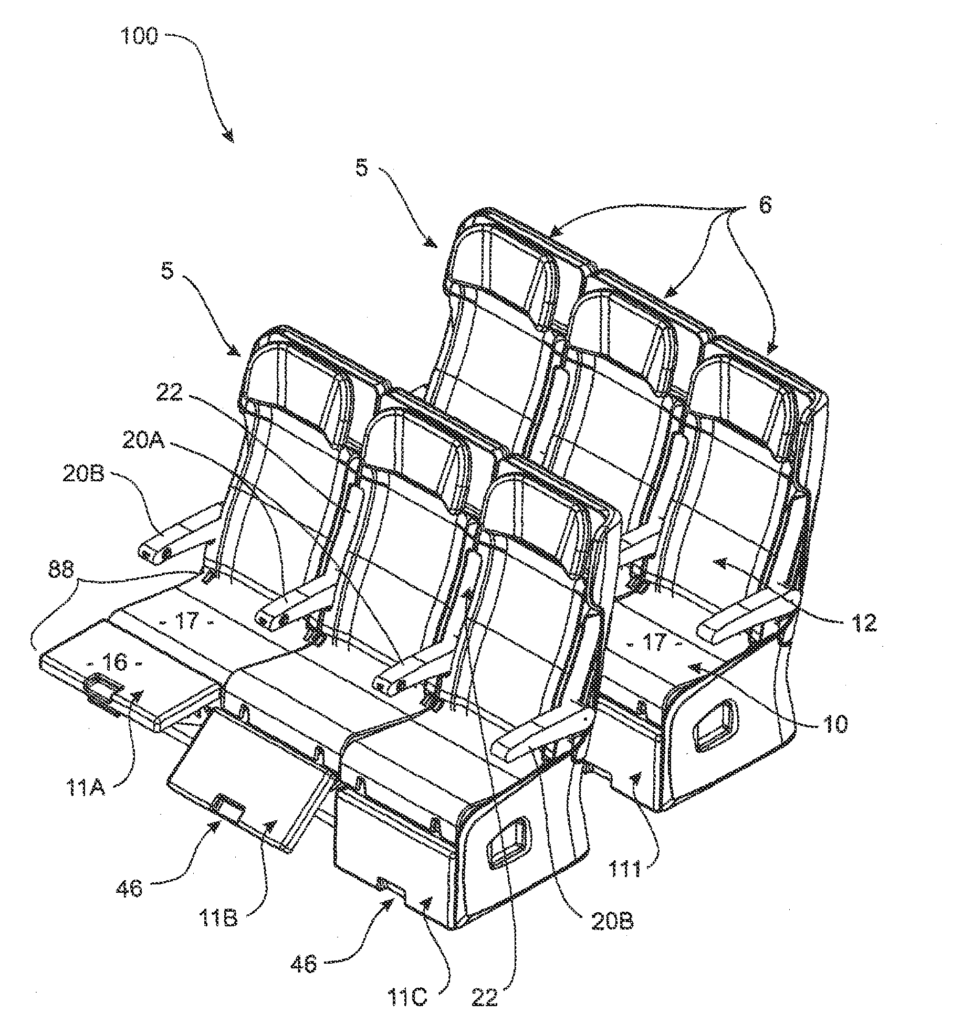

Armrest research from the Air Travel Design Guide: Patent for airplane seats showing ambiguity of armrest spatial “ownership” for middle seats

It’s a reminder that, not so long ago, international flight excited and inspired us—before the realities of delayed flights, lost luggage, rude customs officials, and poorly planned infrastructure stole our dreams. And that’s before we ever stepped onto the plane itself. According to the Air Travel Design Guide, the social contract of air travel has now become so skewed from the original glamorous proposition that today, “the passenger can feel as if they are at the mercy of nature, airport security personnel, or the airline cabin crew. They are directed where to go, how to move, and even when to go to the bathroom on the plane.”

Surely it can—and should—be better than this?

“We may not arrive more on time,” the team concludes, “but thanks to the introduction of better design practice—we might enjoy the experience better.”

Learn more about the Laboratory for Design Technologies and its Industry Advisors Group (IAG) partners at research.gsd.harvard.edu/ldt/

Article originally published on the GSD website and written by Mark Hooper.